Last week, I attended a PGA HOPE event, the Professional Golf Association’s outreach to veterans. PGA HOPE (Helping Our Patriots Everywhere) is the flagship military program of PGA REACH, the charitable foundation of the PGA of America. PGA HOPE introduces golf to Veterans and Active Duty Military to enhance their physical, mental, social and emotional well-being.

Last week, I attended a PGA HOPE event, the Professional Golf Association’s outreach to veterans. PGA HOPE (Helping Our Patriots Everywhere) is the flagship military program of PGA REACH, the charitable foundation of the PGA of America. PGA HOPE introduces golf to Veterans and Active Duty Military to enhance their physical, mental, social and emotional well-being.

My participation in a PGA golf event is both ironic and humorous. I’m anything but a professional golfer. My handicap is my waist line. I would love to shoot my age but I am going to have to live a long time to make that happen. On some days, I would settle for shooting my weight.

This is Master’s Week at Augusta. Legendary TV announcer, John Derr, covered the Master’s for CBS for three decades. One day, he was playing golf with Lou Holtz, legendary football coach, and Lou was having a tough round. Lou recalls the event this way: “The next hole, I hit another bad shot and started cussing, then I threw my club. John had had enough and said, ‘Lou, I see the best players in the world every week, and all I can tell you is, you’re not good enough to get mad.’ I haven’t thrown a club since.”

Back to PGA HOPE. One of the teaching pro’s instructed us on ball position and ball strike. His instruction on ball position and swing path reminded me of something I heard a long time ago. Golf is a game of opposites. If you want the ball to go up, you must hit down. When you swing left, the ball travels right. If you swing right, the ball goes left. Swing easy to hit the ball hard.

Like life, golf is filled with paradoxes—a seemingly self-contradictory statement that is true but defies first-glance logic. It contradicts, confirms, and confounds in the same thought.

The first paradox of war is that though we left the war it did not leave us—it has tremendous staying power. The second paradox of war is: We came home with a new sense of normal that was anything but normal. Our new, post-war normal looked nothing like our old, pre-war normal. Normal in a combat zone did not translate easily into normal at home. Nightmares, flashbacks, panic attacks, depression, anger, anxiety, and hypervigilance became our new normal. We felt unprepared because they trained us to fight the war, not live the peace. Three things shaped our new normal.

One, though truth is often called the first casualty of war, I disagree. I believe the loss of innocence is the first casualty of war. War welcomes warriors to a new normal. We left Vietnam as different people than when we arrived. Adolescence found no refuge in war. They called us “cherries” and “FNG’s” until we weren’t. The loss of innocence—our sacrificed virginity—included the knowledge of what people can do in war, good and bad. We could not un-see or un-hear any of this nor should we, lest we forget.

Two, we left country carrying a duffle bag filled with a profound sense of unfinished business. This haunting phenomenon resulted from something I called pugna interruptus—war interrupted. Our DEROS (date estimated return from overseas) ended our tours of duty. We used DEROS as a verb. We derosed to the world, our term for home. What did we leave behind? When I derosed, I left behind friends to finish the job. Too this day, we often joke: “What the hell happened—we were winning we I left?” Leaving behind friends to mop up turned out to be a significant source of unfinished business for us. Derosing violated the promise, “Leave no man behind.” Our sense of unfinished business manifested in the POW/MIA movement to repatriate the remains of those we left behind. We needed to put a period at the end of that sentence.

Three, survivor’s guilt crowds our pride of service. “Why me?” or “Why did I survive?” or “What makes me so special?” We felt guilty to be home safe while others remained in harm’s way. We felt guilty that our service lacked the ferocity or danger of another’s service. We felt guilty for what we did or did not do in the war. The bizarre psychology of survivor’s guilt paralleled the war experience. Guilt and grief punctuated our new sense of normal.

That we reacted to our experiences proved our humanity. It felt rational to mourn. Like all trauma, war casts a long shadow. We grieved because we cared; it was the cost of doing business. We attempted to cling to the person who went to war—a shadow from our past. Grief anchored us to our humanity, another paradox of war.

This week I will confront another paradox of golf at PGA HOPE: Score less, if I want to win.

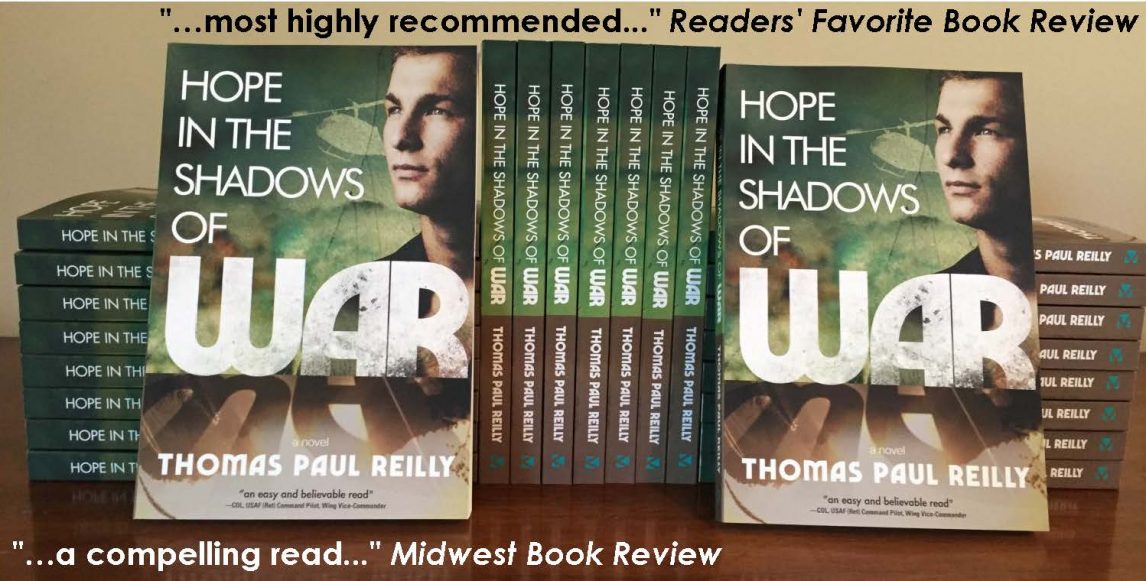

Tom Reilly is the author of Hope in The Shadows of War (Koehler Books, 2018).