War throws a long shadow.

It follows us home and continues to track everything we do and everywhere we go. Young vets run hard from the shadow but discover, there’s no escaping this shadow. We can’t outrun or hide from it. It sticks. Every year we live, the shadow grows longer. As we age, we see this shadow in a light that comes from years of dragging this around.

When we came home from Vietnam, we needed to talk but couldn’t—one of the many paradoxes of war. Besides, no one wanted to hear about it. Heck, in some cases, they didn’t even want us around. They derided our service. Our war wasn’t the big one that our fathers won. Ours was a “police action” in a civil war among Southeast Asians. They told us that we were there to stop the dominoes from falling.

For decades, this shadow taunted us. It awakened in our dreams. The whomp-whomp of Hueys flying overhead transported us back in time to a distant place. Fireworks sparked memories of mortars and rockets that punctuated our sleep. And fresh rain smelled like the jungle. The shadow laughed at our efforts to move on. We carried a chemical in our bodies that changed our DNA and we lost our hearing because no one wears ear plugs in a firefight. We were never going to be the same. VA tried to help, but even they didn’t know what to do.

Then, something profound happened. Terrorists flew planes into the Twin Towers, The Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. Everyone lined up to take their shots of patriotism vaccine. Soon, we began to hear choruses of “Thank you for your service.” Some of us didn’t react well to this. Some wanted say, “Yeah, where the hell was that thirty years ago?” Others smiled, nodded, and accepted graciously the recognition. That purging of guilt became part of the shadow, too.

Now, we wear our hats. We drive vehicles decorated with bumper stickers that showcase our service. Our vanity license plates tell the story of a combat unit that was active fifty years ago. Some display their Red Badges of Courage. As other mature adults adorn fayed college wear, we sport crisp Army, Navy, Air Force, and of course Marine wear—polos, jackets, and patches. This, too, has become part of the shadow.

That this pride persists late in life is one sign of a life well-lived. For some of us, this was the most consequential year of our lives. We did something big enough be proud of, though many of our fellow citizens didn’t view it that way. We offered ourselves up in the service of others, even those who disrespected our service. We always thought we were better than they knew, and now, everyone knows it.

The critics of the Vietnam War have muted their criticism of the warriors. Ken Burns told them it was okay to show compassion for our sacrifice. They liked his story because he is one of them. When people speak of the Vietnam War today, they weigh their words because they know how bitter their words tasted back in the day. Some offer reasons for having not served. I see the disappointment in their eyes. To me, it looks like a case of FOMO. That is part of their shadow.

I’ve gotten to know my shadow well over the past 53 years. I have observed his mimicking everything I do, a pseudo-conscience. I’ve written about him several times, and when I decided to give him center stage in my novel, he thrived. He rested at night when I rested. He enjoyed the recognition of a grateful nation, even though it was a long time coming. Every week, we visit the shadows of our brothers and sisters at JBNC—he appreciates the peace there. My shadow even likes his visits to VA. He feels that they treat him pretty damn good. Mostly, he and I share a pride that fewer than seven percent of the US population know. I’m okay dragging this shadow around for the rest of my journey. I’m kinda proud of the old boy.

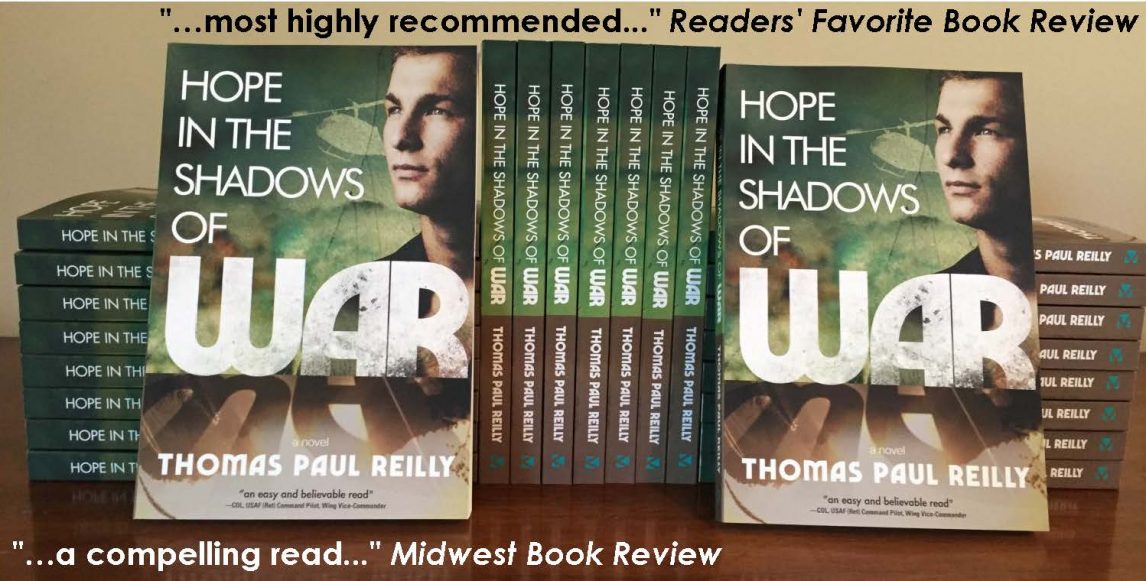

Tom Reilly is the author of Hope in The Shadows of War