On January 30, 1968, South Vietnamese citizens celebrated the Lunar New Year, known as Tet. Tens of thousands of North Vietnamese soldiers and Viet Cong guerilla fighters launched coordinated attacks on more than one hundred towns, villages, and firebases throughout South Vietnam. The Tet Offensive contradicted “the big lie” of a weak and unorganized enemy perpetrated by the Johnson Administration. It seared into the American psyche names like Hue, Khe Sanh, Bien Hoa, and Long Binh. The Tet Offensive devasted Ben Tre, a small village in the Mekong Delta. After its destruction, an American military official told Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett, “It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it.” This widely reported quote introduced the American public to the paradox of war—that to save something we first needed to destroy it.

On January 30, 1968, South Vietnamese citizens celebrated the Lunar New Year, known as Tet. Tens of thousands of North Vietnamese soldiers and Viet Cong guerilla fighters launched coordinated attacks on more than one hundred towns, villages, and firebases throughout South Vietnam. The Tet Offensive contradicted “the big lie” of a weak and unorganized enemy perpetrated by the Johnson Administration. It seared into the American psyche names like Hue, Khe Sanh, Bien Hoa, and Long Binh. The Tet Offensive devasted Ben Tre, a small village in the Mekong Delta. After its destruction, an American military official told Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett, “It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it.” This widely reported quote introduced the American public to the paradox of war—that to save something we first needed to destroy it.

In the fall of 1968, I attended Saint Louis University as a first-semester freshman. One day while using the men’s room of the Student Union, I found myself gaping at the graffiti on the walls—college-student social media in those days. It read: “Fighting for peace is like fornicating for chastity.” This bathroom maxim introduced me to the paradox of war.

A few months later, I entered basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, followed by infantry school at Fort Lewis, Washington. Within the span of a few short months, I went from reading war graffiti on the wall of the men’s room at Saint Louis University to experiencing the war in the jungles of Vietnam, first as an infantryman and later as a helicopter door gunner. Like everyone that served in the Vietnam War, I experienced the paradoxes of war, first in Vietnam and then upon my return to the United States. War has incredible staying power. It rages long after the battle is done.

This paradox of war shadowed us when we returned home—though we left the war, the war did not leave us. It lurked just beneath the surface, and it didn’t take much to trigger memories: a faded photograph; the sound of a helicopter; the smell of rain; the weight of old dog tags; or the taste of bad coffee and warm Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. For me and other Vietnam veterans, the distance in time and space between then and now was as thin as an eyelid. Sleep offered no refuge; on the contrary, it woke old memories. Without beeswax for our ears and bindings on our limbs, we rowed to the sirens’ calls of our memories.

After the Confederate Army’s crushing victory at Fredericksburg, Virginia, Robert E. Lee supposedly uttered these words to his right-hand man, General James Longstreet, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.” He foretold the journey home of Vietnam veterans. A by-product of this first paradox of war surprised us. We missed the war. Not the bullets and blasts but the brotherhood that bound us. At a spiritual retreat a few years ago, I met a helicopter pilot who told me that after his second tour, all he wanted to do was return to Vietnam.

Two weeks after I returned from Vietnam, my wife and I married. One month later, she found me sitting in front of a blank TV screen, four beers into a six-pack, missing my friends whom I left behind. I can only imagine what this young bride must have thought of her soldier.

To non-veterans, it must seem odd that we read war stories, watch war movies, and peruse old photographs. Some even tour yesterday’s battlefields. Revisiting our youth, expended in war as so much ammunition, is an attempt to make sense of what happened.

Remembering is a conscious act and begs the question, “Why would we want to remember?” Many people, including well-meaning family members and friends advised, “Forget about the war, it’s over.” It’s not. It’s like telling adults to forget about high school or college experiences. Imagine telling 9-11 survivors to forget that day. As important parts of our lives, these experiences must find a resting place in our psyches. To forget discounts the value of our experiences and diminishes our service. If our service was deemed valuable to our country then, why should we forget the war now?

It makes psychological sense that we Vietnam veterans do not want to forget our service. The Vietnam War remains a defining time in our lives. By remembering the war and the horrors associated with it, we hang on to our humanity. Being shocked at war is a rational response. Some of us prefer not to revisit our experiences, and that’s okay, too. Everyone processes trauma differently. As we revisit and process our war, we attempt to integrate these life experiences into our psyches. Remembering retrofits our past with our present.

As I age and my eyesight weakens, my vision improves. I now see how the pieces fit. Life was never meant to be lived as a straight line. It turns and twists and we meander through it. Then, our anthem was the Animals song, “We gotta get out of this place.” It will be the last thing we ever do.

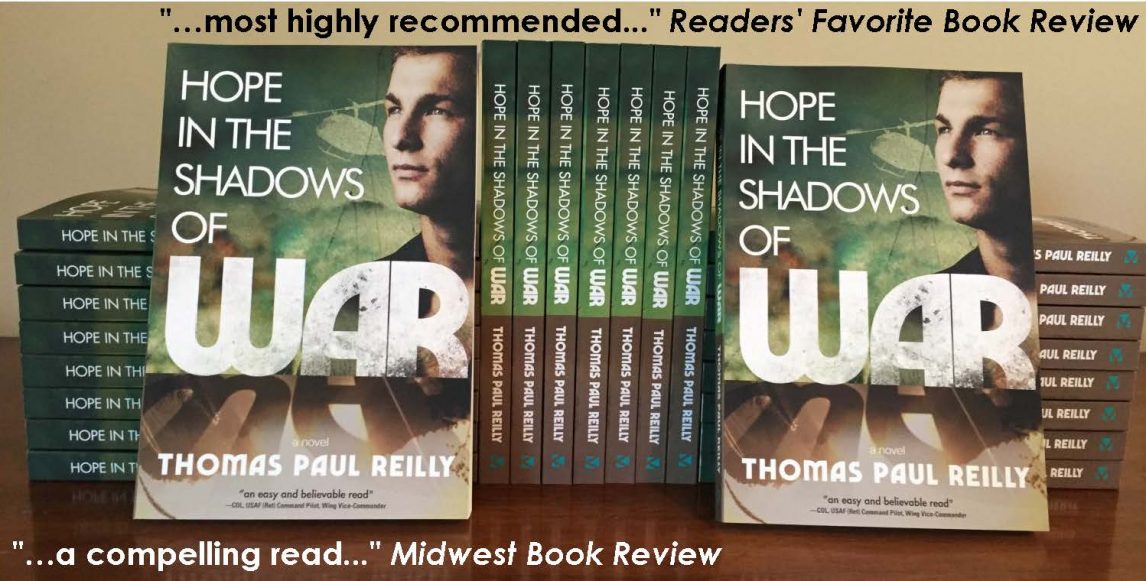

Tom Reilly is the author of Hope in The Shadows of War ( Koehler Books, 2018).